Making sense of ESG reporting—an introduction to the landscape

As global consciousness of the need for climate action increases, the drive to be more sustainable, by cutting emissions and switching to cleaner energy sources is high on the agenda for most industries and powerful economies. To bring about any change, measurement is essential and as Peter Drucker, the father of modern management, said: “what gets measured gets managed”. net-zero targets by 2050. However, what initially seemed like a singular problem, has now exploded into a plethora of acronyms and definitions for sustainability performance. For example, excerpts from SLB’s sustainability report read:

“Our sustainability reporting is guided by our stakeholders and third-party frameworks, including:

- Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB)

- Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD)

- UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights Reporting Framework

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

We take a ‘no one size fits all’ approach to sustainability, and our local teams are aligned globally and empowered to use the UN SDGs as a framework to identify different value creation possibilities in connection with business and stakeholder activities”

The sheer number of acronyms in the above statements, and other similar documents, may be confusing, but the reporting landscape can be made more comprehensible by categorizing them into logical groups, based on stakeholder objectives.

Company GHG compliance reporting is coming! The genealogy from the Paris Agreement to legislated compliance reporting

The landmark Paris Agreement in 2015 (COP 21), a legally binding international treaty on climate change, was adopted by 196 parties who agreed to hold the increase in the global average temperature to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”

Under the agreement each party is responsible for driving progress and reporting their emissions through nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Carbon emissions improvements will be achieved through means that include the use of taxes and policies to disincentivize emissions and incentivize decarbonization actions. These policies are managed by agencies or departments appointed by each country and have their own take on reporting requirements.

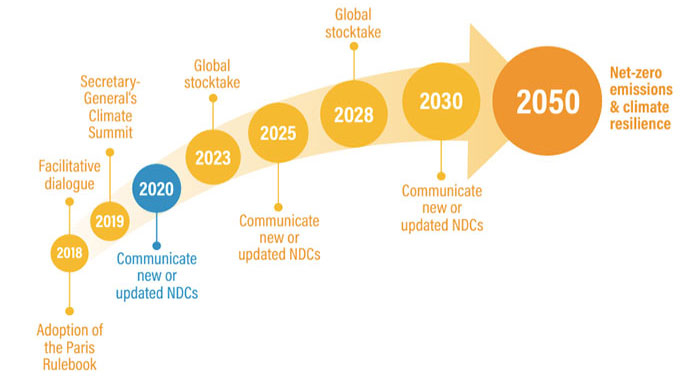

Figure 1. Ambition Mechanism of the Paris Agreement (Source: WRI)

At a national level, each country needs to understand their own emissions, to track and report progress of their NDCs to the UN. This is done via their specific agency or department, which consolidates emissions data from all industries for all greenhouse gases (GHG). This is no different to an oil and gas national data repository (NDR). In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) is responsible for this action. In the UK, the Office of National Statistics (ONS) plays this role by combining data from various sources.

Examples of areas where local carbon pricing mechanisms are already in place, are in emissions trading schemes (ETS) and carbon taxes, for which detailed emissions data is collated by specified authorities. These schemes typically apply only to facilities or installations for hard-to-abate sectors. Reporting accuracy is critical, as the amount emitted has financial implications and metrics must be verified by an accredited body before submission to relevant authorities. The World Bank provides comprehensive information on this topic by country and jurisdiction.

As the impact of climate change increases, legislators are stepping in to expand corporate sustainability disclosures—with the primary aim of informing companies’ investors of their sustainability performance and associated risks in the short and long term. The leading example of this is the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) that mandates EU member countries to legislate sustainability reporting according to the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). These reporting requirements apply to both listed and non-listed companies with different schedules and requirements depending on their size and status. The EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) is the pre-cursor to the CSRD and remains in force until completely replaced by the EU ESRS, which was made law by all EU member states in 2018.

Figure 2. The EU regulatory landscape

Financial conduct authorities run parallel to these regional and global climate legislations, (e.g. US Securities and Exchange Commission (US SEC) to bring that information to the investor community. They may apply the specific country legislated disclosure requirements or adopt the global standards. The US SEC proposed ESG disclosures in 2022, but the details are yet to be finalized, and there are indications that similar agencies in other countries are doing the same. Many of them are leveraging the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) standards, developed by the globally recognized International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). The Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative database tracks the sustainability imperative of the leading stock exchanges globally and includes information which can be utilized by the investment community.

In a study conducted by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in 2023, it was found that 71 stock exchanges worldwide now have guidance on ESG disclosures, compared to only 13 in 2015. According to the UN Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative (SSE) mandatory rules are now in place in 27 markets. Of these markets, 16 are in emerging economies, predominantly in Asia, South America, and Africa.

Governments and local jurisdictions are evaluating whether they should adopt the ISSB or IFRS standards, or any other standard they see fit, including potentially developing their own. For example, the UK government has chosen to endorse the ISSB with their Sustainability Disclosure Standards (SDS), while the EU has chosen to develop their own in the form of the ESRS. It is understandably a complex mix of directives, legislations, rules, and standards—each with differing definitions, implementation timelines, applicability, and quirks. Even at a national level, the rules are changing with parallel efforts between legislators, financial authorities, and industry bodies.

It is important to remember that legislators decide which standard to use, how they should be applied to different companies (e.g. by size, operations footprint), and by when they must be met.

What standards and protocols to follow and how to report? Voluntary reporting, in preparation for compliance reporting

By closely monitoring the evolving global ESG regulatory landscape, we can understand that the time will soon come for reporting to move from voluntary to compliance, as more disclosure requirements are put in place. In the interim, organizations can start preparing their repository now, by choosing a specific rationale for following a particular reporting standard. This can be based on the jurisdiction of their operations or any recognized framework that can be used to establish requirements, boundaries (operational and organizational), and a baseline year. Starting with one standard can help organizations navigate overlapping requirements and allow them to build their capabilities as the complexity in legislation increases.

Laying the data groundwork behind all disclosure

While there are differences between standards, the basis from each rule and standard is typically grandfathered in from earlier voluntary standards (as shown in Figure 4 below).

Figure 3. The evolution of the reporting landscape (Source:IFC)

The details, at least for GHGs, on how quantitative emission metrics are calculated have their roots in the GHG Protocol, which was established in 2000 and has been improved on since. This protocol provides guidance on the sources, calculation methodologies, and emissions factors to use. It should be noted that there are varying degrees of accuracy and leeway, which depend on the maturity of a company’s ability to secure the required information. Guidance is also available to help with prioritization of material sources of emissions, where it is often in an organization’s favor to measure with greater fidelity and accuracy on higher sources of emissions, particularly where carbon taxes or emissions schemes are involved. Other standard boards such as the ISO (specifically ISO 14064-1:2018), British Standards Institution (BSI), and Publicly Available Specification (PAS) have released similar protocols.

The framework for what to disclose and report on has its roots in earlier work, done by Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). A comparison of any two standards or frameworks reveals striking similarities, though they may be structured differently, with generic requirements applicable to all industries and specific requirements applicable only to certain industries. In fact, the ISSB explicitly states that the SASB is a source of guidance, while the EU ESRS is aligned with both the GRI and SASB.

Figure 4. ESG reporting landscape

In the realm of reporting standards, companies should consider voluntary frameworks like the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi), and various other ESG rating agencies. These reporting trackers enable companies to disclose their performance and improvement plans, providing transparency and ESG scores for comparison. Here too, the quantitative calculation of GHGs, for example, is based on the GHG protocol.

The question remains, will these standards, protocols, and methods ever converge? It is hoped that they will, as each standard builds upon those that came before, and countries and jurisdictions continue to conduct their due diligence on which to adopt. Like financial accounting standards which have converged into a limited set of standards such as US GAAP, UK GAAP, and IFRS, ESG compliance standards will also progressively converge to enable easier implementation on a global scale.

If we are to ensure compliance in reporting it will be essential to consider the underlying data necessary for accurate reporting and tracking of quantitative performance. For GHG emissions, the calculation of metrics is based on the GHG protocol, making it crucial to understand the complexities involved in its methodologies.

It might be encouraging to know that when starting out many companies find a significant amount of GHG data has already been collected, which aids in baselining. This is generally done by HSE representatives or facility heads, whereby large emitting facilities are mandated to report emissions to authorities such as the US EPA, EU ETS, or other local jurisdictions. This typically covers most scope 1 emissions for industrial sectors. The next step is to address scope 2 emissions within these facilities, leveraging any requirements for reporting energy usage in certain countries or jurisdictions. Following this, companies must repeat the process for other facilities such as office buildings, warehouses, and transportation fleets, before eventually moving on to understanding emissions from the rest of their value chain.

The larger challenge for most companies is certainly scope 3 and its 15 categories. For industrial companies, including those in oil and gas, the critical scope 3 categories are related to the use phase of products sold (known as downstream scope 3 emissions specifically related to scope 3 category 10, 11 and 12) and that of materials and services purchased (known as upstream scope 3 emissions specifically related to scope 3 category 1 and 2).

In the pursuit of comprehensive scope 1, 2, and 3 measurements, an influx of data and the associated complexities pose an immediate challenge for setting up a baseline of emissions. Companies with numerous global facilities may find themselves managing hundreds of emissions sources within each facility, each with unique emission factors based on location. Additionally, a wide range of products may be sold to various customers through different transportation routes, each with distinct end uses. Measurement for procurement processes alone can involve tens of thousands of purchases and is further complicated by the multitude of suppliers in different regions. This is where an understanding of the entire value chain and leveraging of digital solutions is extremely useful—providing automation in data collection, ontology†, calculations, error-checking, analysis, and the traceability required by audits for compliance.

To meet the requirements of these standards our advanced solutions incorporate optimization capabilities to help determine the decarbonization pathways and specialized digital solutions that provide the detailed engineering support necessary to abate emissions. This is all under a secure scalable data foundation that works to deliver a single source of truth for emissions data

Linking it all together

In summary, organizations need to keep in mind the following fundamental nuances of the compliance sustainability reporting landscape:

- Legislators determine who (i.e. the organizations) within their jurisdictions have to disclose and by when.

- Standards outline what should be disclosed—legislators may adopt existing available standards or create their own, but comparisons across frameworks (including those developed for voluntary disclosure) reveal a lot of similarities.

- Data is the foundation of disclosure—for GHG emissions, the GHG Protocol outlines the data and calculation methodologies that are referred to by the majority if not all standards.

Despite the similarities across standards and frameworks, some disclosure specifics do vary across geographies and jurisdictions. These differences will be covered in more detail in subsequent articles in the series, but points here on who, when, what, to report and the importance of underlying data provide a structure to help better understand the finer nuances of these frameworks.

In addition to compliance reporting, there are voluntary reporting frameworks such as the CDP, GRI, etc., to which disclosure can be made based on their prescribed methodologies. Most standards follow the basic structure of the TCFD framework which encompasses governance, strategy, risk, and metrics. This is a good place for companies to start their journey as they acquire more sophistication in data collection, integration with ERP systems, and understanding of other ESG metrics beyond emissions impacted by their operations. The discussion would be incomplete without the mention of lifecycle analysis (LCA) and product carbon footprints (PCF) that are associated with understanding the emissions footprint across the entire life cycle of a product. An understanding of this is important in order to align with new regulations in cross border adjustment mechanisms, such as the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) for a growing number of sectors like cement, iron, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen.

This was an introduction to the topic, and we hope that it has helped to provide you with a starting point to structure your understanding of the regulatory landscape and drive subsequent steps, particularly for metrics and measurement. Please feel free to reach out directly—we are eager to help you navigate your sustainability journey and drive towards climate action together.

† Technical term for matching disparate data, e.g. matching emission sources with emission factors.

.jpg?la=en&h=1140&w=570&hash=CAB008A645BAAC15600601226C8C476B)